The Night Data Spoke: Unmasking a Fraudster Network

I’ll Never Forget That Night… (I just might forget it eventually, not Mike Ross 😅)

Lemme be a little dramatic 😁

It was December 2021 — a night that changed the way I saw fraud forever. I secured nearly 67 lac PKR from a duplicate payment.

After an eye-opening 😲 dinner with our CFO, I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was off. I started digging, learning everything I could about referral fraud (Or did I 😛).

Then, as time passed, I almost forgot about it …(see told you I’m not Mike Ross)… until a recent conversation with a fellow colleague brought it back to the forefront.

For my own curiosity, I dove deep once again. Since I can’t name the actual case, I’ll call it “Jabba Jabba Bank”

At JABBA JABBA BANK, the analytics team was facing an escalating challenge. Referral rewards were being exploited by fraudsters creating duplicate and vanity accounts solely to trigger sign-up bonuses.

Wait… Haven’t you ever exploited these referrals and signups😏😏

Well getting back… For every new fraudulent referral, the bank was dishing out $$ Y 💲🤑🤑 (can’t use X — kahin Elon saien Bura na manajaye 😂) without any genuine customer engagement.

It wasn’t just about a few stray cases; I observed that around 5% of accounts were driving over 30% of the referral rewards — a red flag I couldn’t ignore.

A Data-Driven Approach

I took a divided strategy to identify and root out this fraud:

- Social Network Analysis:

I built a directed network where each node represented an account (or “person”) and each edge denoted a referral from an originator to a beneficiary.

By calculating network metrics such as:

- Degree: (How many connections each account has)

- Closeness: (How quickly an account can reach all others)

- Betweenness: (How often an account serves as a bridge between different parts of the network)

- Community Detection: (Clustering can reveal groups of accounts that might be working together fraudulently.)

I discovered that a small percentage of accounts were triggering a huge number of referral rewards — up to 30% of our total rewards were being funneled through just 5% of accounts.

Benford’s Law Analysis:

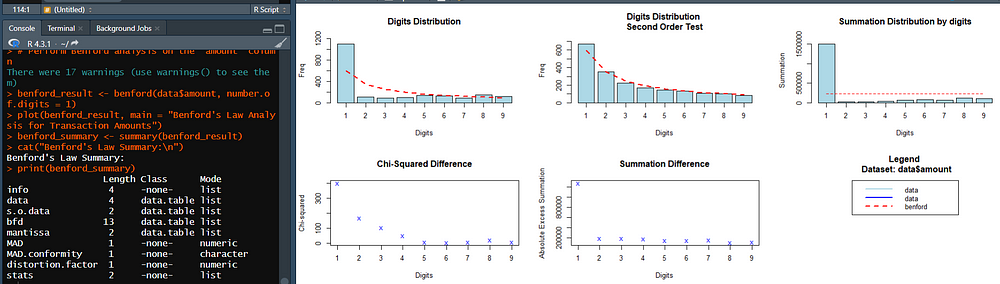

I also examined the transaction amounts — the rewards disbursed for each referral. Benford’s Law tells us that in naturally occurring datasets, lower digits (like 1 or 2) appear as the first digit far more frequently than higher ones. When we compared the observed distribution of the first digits in our rewards data to what Benford’s Law predicts, we found significant deviations.

Let me share the details of how:

1. Digits Distribution (First Order Test):

- The bar chart in the top-left shows the actual frequency of leading digits in your data (blue bars) compared to the expected Benford distribution (red dashed line).

- Observation: The leading digit “1” is overrepresented compared to the expected proportion, while some higher digits (e.g., “6” to “9”) appear to be underrepresented. This indicates a possible deviation from Benford’s Law, especially for higher digits, which could suggest manipulation in the data.

2. Digits Distribution (Second Order Test):

- The second-order test (top-right) examines patterns in the second digit. It also shows some deviations, although these are less pronounced than the first-order test.

- Observation: While the overall trend somewhat aligns with Benford’s Law, the discrepancies are noticeable and might warrant further investigation, particularly for digits “1” and “2.”

3. Chi-Squared Difference:

- The plot in the bottom left shows the chi-squared values for each digit, measuring the difference between observed and expected frequencies.

- Observation: Digit “1” has a much higher chi-squared value than others, indicating significant deviation. Other digits show moderate or low chi-squared differences.

4. Summation Difference by Digits:

- The summation difference (top-center and bottom-right plots) quantifies the absolute excess summation for each digit.

- Observation: Digit “1” contributes disproportionately to the total summation. This is another red flag suggesting anomalies in transactions with amounts starting with “1.”

5. Benford Summary Output:

- MAD (Mean Absolute Deviation):

In the image, the deviations in the plots suggest that MAD exceeds 0.04, falling into the “non-conformity” range. - MAD.conformity:

If labeled as “non-conformity,” this is a strong indicator of potential fraud or data manipulation. - Distortion Factor:

If the distortion factor is unusually high (e.g., >2), this reinforces the conclusion of irregularities.

Benford’s law leads us:

The data shows significant deviations from Benford’s Law, particularly in the overrepresentation of the digit “1” and the underrepresentation of higher digits. These anomalies, combined with high chi-squared values and summation differences, are consistent with patterns of potential fraud or manipulation.

- Filter Suspicious Transactions:

Focus on transactions starting with the digit “1” or other overrepresented digits.

suspicious_transactions <- data %>% filter(substr(as.character(amount), 1, 1) == “1”)

- Investigate Source Accounts:

Identify accounts linked to these transactions and check for unusual activity (e.g., unusually high frequency or amounts).

Such anomalies suggested that some transaction amounts were not naturally occurring, further confirming the presence of fraudulent activity.

Cross-Validation for Precision

The true breakthrough came when I combined these two methods. By cross-referencing the suspicious nodes from the network analysis with the transactions flagged by Benford’s Law, I improved on the most common cases of referral fraud. This dual-validation approach provided my client with a focused list of accounts and transactions that warranted further investigation.

Why It Matters for the Industry

Referral fraud isn’t unique to fintech. Companies like CAREEM, UBER, InDrive, YANGO, NAYAPAY, SADAPAY, and others face similar challenges in managing referral and promo code abuse. By leveraging data science and network analysis:

- Careem and UBER can ensure that ride referrals are genuine, protecting their marketing spend and maintaining customer trust.

- InDrive and YANGO could similarly monitor their user networks to detect duplicate or fraudulent sign-ups.

- NAYAPAY and SADAPAY can use these techniques to secure their digital onboarding processes, ensuring that rewards and bonuses go only to legitimate new users.

In Summary

Using a blend of social network analysis and Benford’s Law, JABBA JABBA BANK was able to visualize and quantify suspicious referral behavior. This method not only provided clear, actionable insights but also demonstrated a scalable approach that companies like CAREEM, UBER, InDrive, YANGO, NAYAPAY, and SADAPAY can adopt to safeguard their referral programs and optimize their fraud prevention strategies.

This isn’t just theory — it’s a practical, proven approach that can help any company fight referral fraud.

Lemme know if you need this done on your data too 😉. Always value for money 😎